"Attica! Attica! Attica! Attica!"

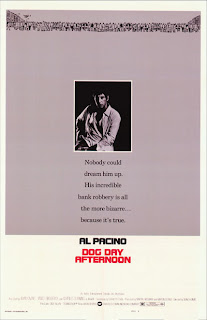

You've probably seen that clip as part of a montage, perhaps during the Oscars or maybe on the AMC Channel or Turner Classics. It's where a young Al Pacino is marching back and forth on the sidewalk shouting "Attica!" at the cops while bystanders cheer him on. I'd seen that during Oscar montages for years before I knew what film it was from: Dog Day Afternoon, the 1975 Sidney Lumet film that won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay and was nominated in a bunch of other categories, including Director, Picture, Actor (Pacino), and Supporting Actor (Chris Sarandon). Even after I knew where that clip came from, I put off seeing the film for years. Finally, after seeing the clip for the umpteenth time during the 2002 Oscars, I caved and rented it. Well, part of the reason I rented it is because it was so easy to do. I joined Netflix in June of '02. Within a month of joining, I saw Dog Day Afternoon. I remember being surprised at the humor in it. Seriously you've got a lot of hilarious laugh-out-loud scenes in the bank. I guess with the "Attica!" clip I was expecting something heavier on the drama, but this flick's got just as much comedy as drama. A few years later I saw it on the big screen at the ArcLight Hollywood as part of their ongoing American Film Institute (AFI) series. Tonight was the first time I'd seen it since then.

It was shown as part of a double bill with Citizen Cohn, the 1992 HBO original movie with James Woods playing asshole lawyer Roy Cohn. What do these two films have in common, you ask? Frank Pierson. The lone Oscar Dog Day Afternoon got for screenwriting? That went to Frank. Citizen Cohn is one of a handful of films he's directed. When it was on HBO, I recorded it and watched it a lot. James Woods is awesome, but I was just as fascinated with the character he was playing. I'd never heard of this guy. Whenever you hear about the Red Scare, McCarthy's the first name anyone mentions, but apparently Roy Cohn was his engine. And then he went on to represent the mafia and whatnot. He was a real bastard. It was just after this that HBO did Stalin with Robert Duvall, which I talked about in my December Crazy Heart post. Those two films sort of connect since it was the Rosenberg convictions that boosted Roy Cohn's career, and the Rosenbergs were convicted for stealing American nuclear secrets and selling them to Stalin. Before tonight, I hadn't seen Citizen Cohn since the early nineties, and I certainly had never seen it on the big screen as it's a made-for-TV movie. I didn't necessarily need to see Dog Day Afternoon again, but it is awesome. I suppose, though, the chance to see Frank Pierson in person was the real draw.

I've actually seen him one other time. Well I didn't see him, I heard him. In August of 1999, a year after I moved out here, the Laemmle Theatre in Santa Monica put on a festival of Westerns. For you non-LA folk, the Laemmles are a local chain of about ten or so theaters that specialize in independent and foreign films. They're run by a father and son, Robert and Greg Laemmle. It was Robert's dad Max and uncle Kurt who opened the first Laemmle in 1938. Get this: The brothers Max and Kurt had this cousin named Carl Laemmle. Don't know who he is? Oh, Carl was no one really. He only founded Universal Pictures, that's all. Anyway, every few years a couple Laemmles will show one Western a week for several weeks in the summer. In August of '99 the one in Santa Monica was one of the chosen venues. I was living at USC at the time. Santa Monica was just a hop and a skip down the 10 freeway, so getting there for the 11 a.m. show wasn't a big deal. Living in the Valley as I do now, and being ten years older, getting up that early to go that far on a Sunday would be, *ahem*, more complicated. One of the Westerns they showed that year was Cat Ballou. Now I'd already seen Cat Ballou once or twice in the eighties when I was in elementary school, living in Jersey with my dad and stepmom. My dad bought Cat Ballou on Beta. He was really excited about it and insisted the kids watch it with him. When you're that young and your parents are into something, by default that means you're not supposed to like it, right? It's not cool. But I actually liked it. Lee Marvin's hilarious, and Jane Fonda's hot. When the Laemmle Santa Monica Fourplex showed it as part of their Western series, I hadn't seen Cat Ballou in over ten years. I figured why not? I'd probably enjoy it more as an adult than I did as a kid. And Jane Fonda would still look hot. So I got there early (I used to get to movies extra early all the time, a quirk I've since grown out of). While I was sitting there waiting for the movie to start, I hear this older guy behind me call out to someone a few rows away, "Hey so-and-so, I'm Frank Pierson." I sat there and thought, "Hmm... Frank Pierson. Where do I know that name?" Soon I realized this was the guy who directed Citizen Cohn. I hadn't seen Citizen Cohn in several years at that point, but I'd seen it often enough that I remembered the name Frank Pierson in the opening credits as the director. I really like the opening credits of Citizen Cohn, with the archival footage of the bomb and the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings and the voiceover by J. Edgar Hoover and so on. It perfectly sets up the mood for the first half of the film, which dramatizes Cohn's work with McCarthy from 1952-54. So I'm thinking to myself, "That's cool. The guy who directed Citizen Cohn's sitting right behind me on a Sunday morning as we take in a show of Cat Ballou. Random as all hell. But cool." Then the movie starts. And what do I see in the opening credits? Screenplay by Frank Pierson. Yes, as it turns out, Frank Pierson used to be quite the screenwriter.

a big deal. Living in the Valley as I do now, and being ten years older, getting up that early to go that far on a Sunday would be, *ahem*, more complicated. One of the Westerns they showed that year was Cat Ballou. Now I'd already seen Cat Ballou once or twice in the eighties when I was in elementary school, living in Jersey with my dad and stepmom. My dad bought Cat Ballou on Beta. He was really excited about it and insisted the kids watch it with him. When you're that young and your parents are into something, by default that means you're not supposed to like it, right? It's not cool. But I actually liked it. Lee Marvin's hilarious, and Jane Fonda's hot. When the Laemmle Santa Monica Fourplex showed it as part of their Western series, I hadn't seen Cat Ballou in over ten years. I figured why not? I'd probably enjoy it more as an adult than I did as a kid. And Jane Fonda would still look hot. So I got there early (I used to get to movies extra early all the time, a quirk I've since grown out of). While I was sitting there waiting for the movie to start, I hear this older guy behind me call out to someone a few rows away, "Hey so-and-so, I'm Frank Pierson." I sat there and thought, "Hmm... Frank Pierson. Where do I know that name?" Soon I realized this was the guy who directed Citizen Cohn. I hadn't seen Citizen Cohn in several years at that point, but I'd seen it often enough that I remembered the name Frank Pierson in the opening credits as the director. I really like the opening credits of Citizen Cohn, with the archival footage of the bomb and the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings and the voiceover by J. Edgar Hoover and so on. It perfectly sets up the mood for the first half of the film, which dramatizes Cohn's work with McCarthy from 1952-54. So I'm thinking to myself, "That's cool. The guy who directed Citizen Cohn's sitting right behind me on a Sunday morning as we take in a show of Cat Ballou. Random as all hell. But cool." Then the movie starts. And what do I see in the opening credits? Screenplay by Frank Pierson. Yes, as it turns out, Frank Pierson used to be quite the screenwriter.

a big deal. Living in the Valley as I do now, and being ten years older, getting up that early to go that far on a Sunday would be, *ahem*, more complicated. One of the Westerns they showed that year was Cat Ballou. Now I'd already seen Cat Ballou once or twice in the eighties when I was in elementary school, living in Jersey with my dad and stepmom. My dad bought Cat Ballou on Beta. He was really excited about it and insisted the kids watch it with him. When you're that young and your parents are into something, by default that means you're not supposed to like it, right? It's not cool. But I actually liked it. Lee Marvin's hilarious, and Jane Fonda's hot. When the Laemmle Santa Monica Fourplex showed it as part of their Western series, I hadn't seen Cat Ballou in over ten years. I figured why not? I'd probably enjoy it more as an adult than I did as a kid. And Jane Fonda would still look hot. So I got there early (I used to get to movies extra early all the time, a quirk I've since grown out of). While I was sitting there waiting for the movie to start, I hear this older guy behind me call out to someone a few rows away, "Hey so-and-so, I'm Frank Pierson." I sat there and thought, "Hmm... Frank Pierson. Where do I know that name?" Soon I realized this was the guy who directed Citizen Cohn. I hadn't seen Citizen Cohn in several years at that point, but I'd seen it often enough that I remembered the name Frank Pierson in the opening credits as the director. I really like the opening credits of Citizen Cohn, with the archival footage of the bomb and the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings and the voiceover by J. Edgar Hoover and so on. It perfectly sets up the mood for the first half of the film, which dramatizes Cohn's work with McCarthy from 1952-54. So I'm thinking to myself, "That's cool. The guy who directed Citizen Cohn's sitting right behind me on a Sunday morning as we take in a show of Cat Ballou. Random as all hell. But cool." Then the movie starts. And what do I see in the opening credits? Screenplay by Frank Pierson. Yes, as it turns out, Frank Pierson used to be quite the screenwriter.

a big deal. Living in the Valley as I do now, and being ten years older, getting up that early to go that far on a Sunday would be, *ahem*, more complicated. One of the Westerns they showed that year was Cat Ballou. Now I'd already seen Cat Ballou once or twice in the eighties when I was in elementary school, living in Jersey with my dad and stepmom. My dad bought Cat Ballou on Beta. He was really excited about it and insisted the kids watch it with him. When you're that young and your parents are into something, by default that means you're not supposed to like it, right? It's not cool. But I actually liked it. Lee Marvin's hilarious, and Jane Fonda's hot. When the Laemmle Santa Monica Fourplex showed it as part of their Western series, I hadn't seen Cat Ballou in over ten years. I figured why not? I'd probably enjoy it more as an adult than I did as a kid. And Jane Fonda would still look hot. So I got there early (I used to get to movies extra early all the time, a quirk I've since grown out of). While I was sitting there waiting for the movie to start, I hear this older guy behind me call out to someone a few rows away, "Hey so-and-so, I'm Frank Pierson." I sat there and thought, "Hmm... Frank Pierson. Where do I know that name?" Soon I realized this was the guy who directed Citizen Cohn. I hadn't seen Citizen Cohn in several years at that point, but I'd seen it often enough that I remembered the name Frank Pierson in the opening credits as the director. I really like the opening credits of Citizen Cohn, with the archival footage of the bomb and the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings and the voiceover by J. Edgar Hoover and so on. It perfectly sets up the mood for the first half of the film, which dramatizes Cohn's work with McCarthy from 1952-54. So I'm thinking to myself, "That's cool. The guy who directed Citizen Cohn's sitting right behind me on a Sunday morning as we take in a show of Cat Ballou. Random as all hell. But cool." Then the movie starts. And what do I see in the opening credits? Screenplay by Frank Pierson. Yes, as it turns out, Frank Pierson used to be quite the screenwriter.I was so young then. Leave it to me to know him only as the director of an HBO movie. As time has gone on and I've expanded my film palette, it's impossible not to chuckle at my twenty-three-year-old self. Anyway, Frank Pierson cut his writing teeth on TV with shows like Have Gun - Will Travel before breaking into the movie biz with Cat Ballou, his first feature script. So of course he'd go see it on a Sunday morning in Santa Monica. The nostalgia value is obvious. And how many chances is he going to get to see his first feature on the big screen anymore? Frank was forty when Cat Ballou came out. I'm thirty-three. There's hope for me yet.

Then he went on to write Cool Hand Luke, which was awesome. I eventually saw that courtesy of Netflix. "What we have here is a failure to communicate!" Classic. He got to try his hand at directing right after that with 1969's The Looking Glass War with Anthony Hopkins. Af ter that he wrote The Anderson Tapes for Sidney Lumet, one of my favorite directors. It was Sid who directed Dog Day Afternoon. Frank then wrote and directed A Star Is Born in '76, followed by King of the Gypsies in '78. He's only directed features sporadically, but he wrote consistently through the seventies and eighties. The last film he wrote was 1990's Presumed Innocent. His bread and butter during his golden years has been directing movies for TV, like Citizen Cohn and Truman for HBO and a whole bunch of other stuff. He's still at it. I have to say how remarkably with it and cogent he is for a man turning eighty-five this spring. More than that, he was a great talker, one of the best interview subjects I've seen at a Q&A, and mind you, I've seen my share. You can't be too surprised. Most writers are eloquent. But the man's almost eighty-five. Please let my genes be that strong.

ter that he wrote The Anderson Tapes for Sidney Lumet, one of my favorite directors. It was Sid who directed Dog Day Afternoon. Frank then wrote and directed A Star Is Born in '76, followed by King of the Gypsies in '78. He's only directed features sporadically, but he wrote consistently through the seventies and eighties. The last film he wrote was 1990's Presumed Innocent. His bread and butter during his golden years has been directing movies for TV, like Citizen Cohn and Truman for HBO and a whole bunch of other stuff. He's still at it. I have to say how remarkably with it and cogent he is for a man turning eighty-five this spring. More than that, he was a great talker, one of the best interview subjects I've seen at a Q&A, and mind you, I've seen my share. You can't be too surprised. Most writers are eloquent. But the man's almost eighty-five. Please let my genes be that strong.

ter that he wrote The Anderson Tapes for Sidney Lumet, one of my favorite directors. It was Sid who directed Dog Day Afternoon. Frank then wrote and directed A Star Is Born in '76, followed by King of the Gypsies in '78. He's only directed features sporadically, but he wrote consistently through the seventies and eighties. The last film he wrote was 1990's Presumed Innocent. His bread and butter during his golden years has been directing movies for TV, like Citizen Cohn and Truman for HBO and a whole bunch of other stuff. He's still at it. I have to say how remarkably with it and cogent he is for a man turning eighty-five this spring. More than that, he was a great talker, one of the best interview subjects I've seen at a Q&A, and mind you, I've seen my share. You can't be too surprised. Most writers are eloquent. But the man's almost eighty-five. Please let my genes be that strong.

ter that he wrote The Anderson Tapes for Sidney Lumet, one of my favorite directors. It was Sid who directed Dog Day Afternoon. Frank then wrote and directed A Star Is Born in '76, followed by King of the Gypsies in '78. He's only directed features sporadically, but he wrote consistently through the seventies and eighties. The last film he wrote was 1990's Presumed Innocent. His bread and butter during his golden years has been directing movies for TV, like Citizen Cohn and Truman for HBO and a whole bunch of other stuff. He's still at it. I have to say how remarkably with it and cogent he is for a man turning eighty-five this spring. More than that, he was a great talker, one of the best interview subjects I've seen at a Q&A, and mind you, I've seen my share. You can't be too surprised. Most writers are eloquent. But the man's almost eighty-five. Please let my genes be that strong.Dog Day Afternoon is based on a true story that took place in Brooklyn on August 22, 1972. This twenty-seven-year-old guy named John Wojtowicz and one of his pals held up a Chase Manhattan bank. He wanted to get money for his boyfriend Ernie's sex change operation. John had two kids from a marriage that was still technically extant. They separated in '69 but still hadn't finalized a divorce. And then in '71 he starts this affair with Ernie, who wants to become a woman and change his name to Elizabeth.

John used to be a bank teller. I suppose he was counting on that knowledge to pull off his heist without incident. Ha. Without incident? First off, of the two guys who were supposed to help him, one bailed right away. He saw a cop car pass by, got spooked, and bolted. That left John with this eighteen-year-old kid named Sal. While Sal was a youngin', he was the only one of the three would-be robbers who had a criminal record. Indeed, Sal's is a sad story. He'd already been in and out of reform school and prison. During one prison stint he was sodomized by his much larger cellmates. He told John before the robbery that he'd rather die than go back to jail.

The cops show up before they can get away with the money, and it becomes a fourteen-hour hostage situation. The news shows up. Crowds form. Lots of negotiating back and forth. John plays the crowd. Sal's extremely nervous and high strung. The NYPD and FBI pretend to go along with John and Sal's demands for a private jet. The two robbers are chauffeured to JFK along with the hostages and a couple FBI agents, one of whom has a gun hidden in the front seat. When they get to the airport, they arrest John and Sal. They yell "freeze" and try to wrestle Sal's gun away from him and end up shooting him in the head. At least Sal wouldn't have to go back to jail and get raped. He was going to use his share of the money to take care of his two sisters, who were living in foster care. Their mom was too drunk to take care of them. Depressing as hell, huh? John, meanwhile, gets a twenty-year sentence. He gets out in fourteen.

In writing the script, Frank Pierson's main source was an article in Life called "The Boys in the Bank" by P.F. Kluge and Thomas Moore. P.F. Kluge, by the way, who's in his sixties now, wrote that one novel Eddie and the Cruisers. And he's written lots of other novels and nonfiction. It's such a small world, isn't it? That Eddie and the Cruisers and Dog Day Afternoon would share the same source? A lot of what you see in the movie really did happen, but as you'll see below in Frank's Q&A, the movie does diverge now and again. For his part, John Wojtowicz always claimed the movie was only 30% accurate. Not sure how he arrived at that number, but as he was the one who caused it all, you've got to extend the would-be crook at least some credibility.

By far the most glaring difference is that the movie version of Sal isn't a teenager. He's played by the late great John Cazale, who was pushing forty at the time. If his name isn't familiar to you, that's because he died of bone cancer three years after Dog Day Afternoon was filmed, in 1978 at the age of forty-three. He'd just finished filming The Deer Hunter. He was also engaged to Meryl Streep. The Deer Hunter director Michael Cimino knew he was sick and dyi ng, but the studio didn't. He wanted to get all of John's scenes shot before the studio found out. Unfortunately that didn't work, but John stayed on because Meryl Streep threatened to quit if he was fired. John only got to make five films before he died: Godfather I and II (he played Fredo), The Conversation, Dog Day Afternoon, and The Deer Hunter. All five of those films were Best Picture nominees. He and Pacino go way back. They were pals in high school. He met Meryl Streep doing theater in New York. Pacino's the one who landed him the audition for Fredo. John's story, like the real Sal's, is poignant, is it not? Unfortunately, though, it's because of the dramatic license of casting him to play Sal that Dog Day Afternoon has its most glaring flaw. In real life Sal was high strung and volatile during the fourteen-hour standoff because he was terrified of going back to jail. He was still emotionally damaged from getting raped during his previous stint. In the movie John Cazale plays Sal as volatile, but we don't know why. All we know is that he'd have no trouble shooting the hostages or the cops or whatever. The movie version of Sal is a sociopath, in other words. Unhinged for no discernible reason.

ng, but the studio didn't. He wanted to get all of John's scenes shot before the studio found out. Unfortunately that didn't work, but John stayed on because Meryl Streep threatened to quit if he was fired. John only got to make five films before he died: Godfather I and II (he played Fredo), The Conversation, Dog Day Afternoon, and The Deer Hunter. All five of those films were Best Picture nominees. He and Pacino go way back. They were pals in high school. He met Meryl Streep doing theater in New York. Pacino's the one who landed him the audition for Fredo. John's story, like the real Sal's, is poignant, is it not? Unfortunately, though, it's because of the dramatic license of casting him to play Sal that Dog Day Afternoon has its most glaring flaw. In real life Sal was high strung and volatile during the fourteen-hour standoff because he was terrified of going back to jail. He was still emotionally damaged from getting raped during his previous stint. In the movie John Cazale plays Sal as volatile, but we don't know why. All we know is that he'd have no trouble shooting the hostages or the cops or whatever. The movie version of Sal is a sociopath, in other words. Unhinged for no discernible reason.

ng, but the studio didn't. He wanted to get all of John's scenes shot before the studio found out. Unfortunately that didn't work, but John stayed on because Meryl Streep threatened to quit if he was fired. John only got to make five films before he died: Godfather I and II (he played Fredo), The Conversation, Dog Day Afternoon, and The Deer Hunter. All five of those films were Best Picture nominees. He and Pacino go way back. They were pals in high school. He met Meryl Streep doing theater in New York. Pacino's the one who landed him the audition for Fredo. John's story, like the real Sal's, is poignant, is it not? Unfortunately, though, it's because of the dramatic license of casting him to play Sal that Dog Day Afternoon has its most glaring flaw. In real life Sal was high strung and volatile during the fourteen-hour standoff because he was terrified of going back to jail. He was still emotionally damaged from getting raped during his previous stint. In the movie John Cazale plays Sal as volatile, but we don't know why. All we know is that he'd have no trouble shooting the hostages or the cops or whatever. The movie version of Sal is a sociopath, in other words. Unhinged for no discernible reason.

ng, but the studio didn't. He wanted to get all of John's scenes shot before the studio found out. Unfortunately that didn't work, but John stayed on because Meryl Streep threatened to quit if he was fired. John only got to make five films before he died: Godfather I and II (he played Fredo), The Conversation, Dog Day Afternoon, and The Deer Hunter. All five of those films were Best Picture nominees. He and Pacino go way back. They were pals in high school. He met Meryl Streep doing theater in New York. Pacino's the one who landed him the audition for Fredo. John's story, like the real Sal's, is poignant, is it not? Unfortunately, though, it's because of the dramatic license of casting him to play Sal that Dog Day Afternoon has its most glaring flaw. In real life Sal was high strung and volatile during the fourteen-hour standoff because he was terrified of going back to jail. He was still emotionally damaged from getting raped during his previous stint. In the movie John Cazale plays Sal as volatile, but we don't know why. All we know is that he'd have no trouble shooting the hostages or the cops or whatever. The movie version of Sal is a sociopath, in other words. Unhinged for no discernible reason.At any rate, Dog Day Afternoon's a great film. It's one of those films that gets better each time you see it. Sure it takes dramatic licenses with reality, but show me a fact-based film that doesn't. Amadeus takes all kinds of liberties with the truth, but it's all for the sake of top-notch drama.

Which leads me to Citizen Cohn, another fact-based drama. This was adapted from a 1987 biography of Roy Cohn by Washington Post writer Nicolas von Hoffman. The movie debuted on HBO in August of 1992, just before I started my junior year of high school. In the spring of 1993 I faced up to reading the book only to discover that the movie had left out so much. The book's huge, almost five hundred pages. Not quite two hours long, the movie barely scrapes the surface of Cohn's life. The main reason to watch it is James Woods. He's awesome. Frank Pierson directed it, but he didn't write the screenplay adaptation. That was taken on by David Franzoni, whose only writing credit at that point was Jumpin' Jack Flash of all things. After this he wrote Amistad, and he co-wrote Gladiator, which is awesome because that won a whole bunch of Oscars, including Best Original Screenplay. That was followed by the bad King Arthur movie with Clive Owen. So his record is spotty, I suppose, but at least he's working, right? Toiling in the trenches and digging up the occasional gold nugget.

The first half of Citizen Cohn focuses on the early 1950s when, only twenty-five or so, Roy Cohn helps Senator Joseph McCarthy persecute innocent Americans. While James Woods is awesome, he is kind of an awkward casting choice for that part of the film. He doesn't pass for twenty-five at all, but you forgive that soon enough. The second half of the movie's kind of weak. I mean Roy Cohn did all kinds of stuff and got involved in all kinds of heinous shit. He ripped people off to the tune of six figures. Some of his clients were New York Mafioso. And that's just the tip of it. But we hardly get to see any of that in the movie. I can just see David Franzoni hunched over his laptop at Starbucks trying to give us a taste of each decade of Cohn's post-McCarthy life until he dies of AIDS in 1986. But in fact we don't get a taste for anything except for what a weirdo asshole Cohn was, and for what an awesome actor James Woods is. I suppose another reason I watched it over and over again was because I'd never heard of the Red Scare before. Or Joe McCarthy. Hey I was sixteen, okay? I was fascinated by the whole thing, that a U.S. Senator could get away with ruining all those innocent lives in public. On TV.

Speaking of TV, about a year after this came out, during my senior year of high school, the Discovery Channel had a documentary on the Army v. McCarthy hearings. That comes halfway into the film. These are the hearings that finally undid McCarthy as he tried leveling Communist spy charges at high-ups in the State Department and the Army. Dude went after generals at Fort Monmouth . Roy Cohn was a big reason he had the cojones to do that. Cohn was carrying on a sort-of affair with this guy named G. David Schine, heir to the Schine family chain of hotels. The same age as Cohn, Schine graduated from Harvard and then wrote this silly little anti-Communist pamphlet called The Definition of Communism. He had it placed in the room of every hotel in his family's entire chain, in the same drawer where they stick the Gideon Bible. I don't know much about it except that it's frivolous, but it did lead to him getting introduced to Roy Cohn at a party. That he was still in the closet didn't stop Cohn from being immediately smitten. He scored (with?) David a position as consultant to the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was all such a joke, of course. What set the final chain of events in motion was when David was forced to enlist in the Army. Indignant that the Army would take away his David, Cohn egged on McCarthy to go after them, which in hindsight seems incredibly stupid, especially since they were fighting the Korean War at the time. They were viewed as patriotic heroes fighting a real Communist threat in North Korea. You think they were going to lie down for a bunch of raving whack jobs?

. Roy Cohn was a big reason he had the cojones to do that. Cohn was carrying on a sort-of affair with this guy named G. David Schine, heir to the Schine family chain of hotels. The same age as Cohn, Schine graduated from Harvard and then wrote this silly little anti-Communist pamphlet called The Definition of Communism. He had it placed in the room of every hotel in his family's entire chain, in the same drawer where they stick the Gideon Bible. I don't know much about it except that it's frivolous, but it did lead to him getting introduced to Roy Cohn at a party. That he was still in the closet didn't stop Cohn from being immediately smitten. He scored (with?) David a position as consultant to the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was all such a joke, of course. What set the final chain of events in motion was when David was forced to enlist in the Army. Indignant that the Army would take away his David, Cohn egged on McCarthy to go after them, which in hindsight seems incredibly stupid, especially since they were fighting the Korean War at the time. They were viewed as patriotic heroes fighting a real Communist threat in North Korea. You think they were going to lie down for a bunch of raving whack jobs?

. Roy Cohn was a big reason he had the cojones to do that. Cohn was carrying on a sort-of affair with this guy named G. David Schine, heir to the Schine family chain of hotels. The same age as Cohn, Schine graduated from Harvard and then wrote this silly little anti-Communist pamphlet called The Definition of Communism. He had it placed in the room of every hotel in his family's entire chain, in the same drawer where they stick the Gideon Bible. I don't know much about it except that it's frivolous, but it did lead to him getting introduced to Roy Cohn at a party. That he was still in the closet didn't stop Cohn from being immediately smitten. He scored (with?) David a position as consultant to the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was all such a joke, of course. What set the final chain of events in motion was when David was forced to enlist in the Army. Indignant that the Army would take away his David, Cohn egged on McCarthy to go after them, which in hindsight seems incredibly stupid, especially since they were fighting the Korean War at the time. They were viewed as patriotic heroes fighting a real Communist threat in North Korea. You think they were going to lie down for a bunch of raving whack jobs?

. Roy Cohn was a big reason he had the cojones to do that. Cohn was carrying on a sort-of affair with this guy named G. David Schine, heir to the Schine family chain of hotels. The same age as Cohn, Schine graduated from Harvard and then wrote this silly little anti-Communist pamphlet called The Definition of Communism. He had it placed in the room of every hotel in his family's entire chain, in the same drawer where they stick the Gideon Bible. I don't know much about it except that it's frivolous, but it did lead to him getting introduced to Roy Cohn at a party. That he was still in the closet didn't stop Cohn from being immediately smitten. He scored (with?) David a position as consultant to the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was all such a joke, of course. What set the final chain of events in motion was when David was forced to enlist in the Army. Indignant that the Army would take away his David, Cohn egged on McCarthy to go after them, which in hindsight seems incredibly stupid, especially since they were fighting the Korean War at the time. They were viewed as patriotic heroes fighting a real Communist threat in North Korea. You think they were going to lie down for a bunch of raving whack jobs?That's another weakness of the film, how it dramatizes the Army v. McCarthy hearings. In reality the hearings lasted six weeks. Now I know when you write a script, time and space are limited. Very limited. Believe me, as someone who's written scripts before, I'm very sensitive to that issue. Still, they didn't have to give it such short shrift. At the very least they could've used some editing or a montage to convey how long and drawn out those hearings were, and maybe show McCarthy starting out as a real threat before the unassuming Boston lawyer Joseph Welch rips him to shreds on national TV. Anyway, for all I know, David Franzoni and Frank Pierson did all of that and more but were forced to trim it down to size by the powers that be at HBO. Who knows?

Interesting thing about G. David Schine. After the whole Army fiasco, he married this Swedish hottie who'd been crowned Miss Sweden and Miss Universe. During his time with Cohn, there was talk that the two of them were having an affair. Well if he was gay, he sure changed his mind. Cohn was such a whacko, maybe he scared the gay out of Schine or something. At any rate, Schine and Miss Sweden married in 1957, the same year, coincidentally, McCarthy died of alcoholism. The happy couple settled in L.A. and had six kids. They were still alive when Citizen Cohn originally aired on HBO. Four years later, though, on a Sunday in June 1996, they crashed and died in their private plane at Burbank Airport. One of their kids was piloting the plane and died as well. And just to show you how old demons can come home to roost, not long after Schine's death the playwright Tony Kushner (Angels in America) wrote a one-act comedy called G. David Schine in Hell. It takes place the day Schine dies and shows him arriving in Hell to be reunited with Roy Cohn. Harsh.

As for the Army counsel Joseph Welch, get this. In 1959, just five years after the hearings, Otto Preminger cast him as a judge in Anatomy of a Murder. Awesome film if you haven't seen it. Welch took the part because he felt it was the only time he'd ever get to be a judge. And if that's not enough, he was nominated for stuff. The Golden Globes nominated him for Best Supporting Actor. In Britain they gave him a BAFTA nom for Best Newcomer. That's wild. Unfortunately he didn't get to ride that high too long. Joseph Welch passed away in 1960.

Anyway, I don't want to get too sidetracked. I'm just trying to show you all this extraneous stuff that happened just outside the bounds of the film's very limited and limiting purview. Honestly, instead of HBO, PBS Masterpiece Theatre would've been a much better venue for adapting Citizen Cohn. There you could have, say, three ninety-minute episodes spread across three Sundays. They do that all the time with other books, although I do have to say they show a bias for nineteenth century writers like Jane Austin, Charles Dickens, and Elizabeth Gaskell. But they adapt more modern stuff sometimes. Citizen Cohn would've been perfect. With four and a half hours instead of not quite two, just think, they could've done so much more. And imagine what James Woods could've done. He really could've mined the depths of Roy Cohn's lunatic psyche.

Frank Pierson didn't say too much about Citizen Cohn during the Q&A, which is understandable given Dog Day Afternoon's much greater stature. First off, the article from Life that served as the source material wasn't really an article per se but an edited compilation of other articles written about the event. The compilation's title, "The Boys in the Bank," was the original title of the film. Frank didn't say who changed it, but thank God for whoever it was. I can't imagine it being called The Boys in the Bank for Pete's sake, especially since the one boy character, Sal, was changed to a man via the casting of John Cazale.

Sidney Lumet had just directed Al Pacino in Serpico. After that, they were a team, Frank said. They wanted to work together again. I'm not sure what he meant by "team" since they never worked together after Dog Day Afternoon. Too bad, too. With Serpico and Dog Day Afternoon, it sort of makes you wonder what else they could've done. Anyway, after Serpico Sidney Lumet was already committed to going to England to shoot Murder on the Orient Express. It's the one with Albert Finney as Poirot. Sean Connery and Anthony Perkins are two of the train passengers. Good stuff if you haven't seen it, although Finney can be grating as Poirot. But that's because Poirot was meant to get on people's nerves. He even got on Agatha Christie's nerves, and she's the one who created him for Pete's sake. While Sidney was doing that, Al Pacino was reprising his role as Don Michael Corleone for The Godfather: Part II. As for Frank, he told us tonight that Sidney and Al's absence meant he worked on the Dog Day script by himself for five months. He tried to be as faithful to the story as possible. And indeed he did retain a lot of stuff that really happened. What he had to do for the sake of dramatic structure was rearrange the order in which events took place throughout the standoff. So when Sal in the movie fires that shot toward the back when he senses the cops might be storming in, that's not the time of day (or night, the standoff lasted fourteen hours) when the real Sal, the teenager, fired the shot toward the back. And yes he really did shoot at the cops. Remember, the real Sal was beyond damaged goods. It was make off with the money or go down in a blaze of glory. As another example, when the pizza man shows up in the film is not really when he showed up during the standoff.

wonder what else they could've done. Anyway, after Serpico Sidney Lumet was already committed to going to England to shoot Murder on the Orient Express. It's the one with Albert Finney as Poirot. Sean Connery and Anthony Perkins are two of the train passengers. Good stuff if you haven't seen it, although Finney can be grating as Poirot. But that's because Poirot was meant to get on people's nerves. He even got on Agatha Christie's nerves, and she's the one who created him for Pete's sake. While Sidney was doing that, Al Pacino was reprising his role as Don Michael Corleone for The Godfather: Part II. As for Frank, he told us tonight that Sidney and Al's absence meant he worked on the Dog Day script by himself for five months. He tried to be as faithful to the story as possible. And indeed he did retain a lot of stuff that really happened. What he had to do for the sake of dramatic structure was rearrange the order in which events took place throughout the standoff. So when Sal in the movie fires that shot toward the back when he senses the cops might be storming in, that's not the time of day (or night, the standoff lasted fourteen hours) when the real Sal, the teenager, fired the shot toward the back. And yes he really did shoot at the cops. Remember, the real Sal was beyond damaged goods. It was make off with the money or go down in a blaze of glory. As another example, when the pizza man shows up in the film is not really when he showed up during the standoff.

wonder what else they could've done. Anyway, after Serpico Sidney Lumet was already committed to going to England to shoot Murder on the Orient Express. It's the one with Albert Finney as Poirot. Sean Connery and Anthony Perkins are two of the train passengers. Good stuff if you haven't seen it, although Finney can be grating as Poirot. But that's because Poirot was meant to get on people's nerves. He even got on Agatha Christie's nerves, and she's the one who created him for Pete's sake. While Sidney was doing that, Al Pacino was reprising his role as Don Michael Corleone for The Godfather: Part II. As for Frank, he told us tonight that Sidney and Al's absence meant he worked on the Dog Day script by himself for five months. He tried to be as faithful to the story as possible. And indeed he did retain a lot of stuff that really happened. What he had to do for the sake of dramatic structure was rearrange the order in which events took place throughout the standoff. So when Sal in the movie fires that shot toward the back when he senses the cops might be storming in, that's not the time of day (or night, the standoff lasted fourteen hours) when the real Sal, the teenager, fired the shot toward the back. And yes he really did shoot at the cops. Remember, the real Sal was beyond damaged goods. It was make off with the money or go down in a blaze of glory. As another example, when the pizza man shows up in the film is not really when he showed up during the standoff.

wonder what else they could've done. Anyway, after Serpico Sidney Lumet was already committed to going to England to shoot Murder on the Orient Express. It's the one with Albert Finney as Poirot. Sean Connery and Anthony Perkins are two of the train passengers. Good stuff if you haven't seen it, although Finney can be grating as Poirot. But that's because Poirot was meant to get on people's nerves. He even got on Agatha Christie's nerves, and she's the one who created him for Pete's sake. While Sidney was doing that, Al Pacino was reprising his role as Don Michael Corleone for The Godfather: Part II. As for Frank, he told us tonight that Sidney and Al's absence meant he worked on the Dog Day script by himself for five months. He tried to be as faithful to the story as possible. And indeed he did retain a lot of stuff that really happened. What he had to do for the sake of dramatic structure was rearrange the order in which events took place throughout the standoff. So when Sal in the movie fires that shot toward the back when he senses the cops might be storming in, that's not the time of day (or night, the standoff lasted fourteen hours) when the real Sal, the teenager, fired the shot toward the back. And yes he really did shoot at the cops. Remember, the real Sal was beyond damaged goods. It was make off with the money or go down in a blaze of glory. As another example, when the pizza man shows up in the film is not really when he showed up during the standoff. I've already explained the big change with Sal's character, but what I didn't say is that the change wasn't Frank's decision. I mean really, why would any writer worth their salt change something that was already so dramatically compelling? He did change it a little. While he kept Sal a teenager, Frank said that when he wrote the script, he introduced him as a "Botticelli angel." In other words, the original movie Sal was a fresh-faced innocent. Hmm, that's interesting. Then how would he have explained Sal's becoming unhinged? Perhaps it would've just been nerves. He was young after all. Anyway, Frank wanted to keep Sal eighteen but get rid of his criminal past and just have him be this innocent kid. And then through the act of the robbery, the John character, Sonny in the film, would essentially be corrupting him by using him as an accomplice. That would be irony since Sonny's intentions in the film, like John in real life, were pure. He just wanted to help his boyfriend. Yet he'd be corrupting this innocent youth to do so. And since the Sonny and Sal characters are Catholic, the corruption would be that much more meaningful. Corrupting the innocent is one of the worst things a Catholic can do.

Interesting, huh? Lot of layers going on there. But it was "thanks" to Al Pacino that Sal's character had to be completely rewritten. Just as Al had helped John land the Fredo role in the Godfather flicks, here he did his good buddy another favor. Frank, as the screenwriter, would have no say in this decision. Even Sidney Lumet had to relent lest Al Pacino quit the project. I suppose with the Godfather films and Serpico and all that, Big Al wielded quite a bit of clout. When Al was done The Godfather: Part II and Sidney was done Orient Express, Frank was done with the script (or so he thought). They all got together to talk about it at Al's house in New York. Al and Sidney really hit it off during Serpico and wanted to work together again. They didn't think it would be another New York-set fact-based drama, but there you go. Everyone has a niche. According to Frank, it was too irresistible not to do. For starters, most of the story, since it was true, was already laid out. Frank had to rearrange some stuff, invent a few other things, change some names, but most of the story was set. The real clincher, Frank told us, was how the real John Wojtowicz bore such a striking resemblance to Al Pacino.

The meeting at Al's house went well for the most part. The main thing that really bugged Al about the script was the Leon character Chris Sarandon ultimately played, based on John Wojtowicz's boyfriend Ernest "Ernie" Aron. In reality, Ernie Aron had kind of a mouth on him. He was the kind of guy who was unafraid of public displays of affection and who indulged in raunchy language without giving it a second thought. So that's the kind of character Frank made Leon. Also in real life, just before John and Sal got in the limo with the FBI agents and bank employees, John and Ernie had a farewell kiss, right there on the street in front of the cameras, cops, and onlookers. Apparently it was quite a kiss. They figured rightly that it'd be their last one, so they made it count. Frank kept that. Al wanted it changed. Sonny and Leon could talk to each other on the phone, but he didn't want them sharing the screen together. When Frank tried to argue, Al got on his knees and barked like a dog. That's weird, I forget if Frank explained why he did that. I think Al was just trying to make a point about why it's not good to have raunchy behavior just for the sake of raunch. He wanted the script to be less sexy/raunchy and more about two people who were doomed never to consummate their feelings for each other. Frank said the script did improve with that change, and Al gets all the credit for that. One thing he said required absolutely no change was Sonny's estranged wife Angie, based on John Wojtowicz's estranged wife Carmen Bifulco. The way Angie sounds in the film and the things she says about how there's no way her man could be the one holding up a bank and goes on and on and on, Frank took all of that verbatim from the Life article.

Before starting the shoot, Sidney took everyone through three weeks of rehearsals. Frank said those three weeks made all the difference in terms of nailing down the script. You can read the thing backward and forward all you want, but it's not until you hear the cast reading the lines and see them acting it out that you can better identify and revise the weak spots. It's interesting hearing how Sidney Lumet spent so much time on rehearsals after I just saw Irish filmmaker Jim Sheridan three weeks ago talking about how he never rehearses. Why rehearse a two-minute scene? He's done a lot of theater, I'm assuming more than Sidney Lumet. As Jim Sheridan said, scenes in a play can go on and on and on, much longer than your average movie scene (Inglorious Basterds notwithstanding). With a lot of that under his belt, he doesn't feel it's worth it for a film. But Sidney Lumet does. Of course money is another factor. Jim Sheridan's films never seem to have much of a budget. And if you want your actors to do several weeks of work before you shoot a foot of film, they have to be paid accordingly. Sidney Lumet and Al Pacino were at their respective zeniths in the mid seventies. I'm sure the studio gave them however much money they wanted. Three weeks of rehearsals would be a luxury to independent filmmakers.

Even though Frank acquiesced to Al's demands, that didn't stop Al from quitting the film, which he did several times, according to Frank. He didn't really elaborate on why Al would be such a vacillating weirdo, especially since Frank and Sidney did whatever he wanted. Or maybe Sidney gave some pushback. Who knows? The punch line here is that every time Al quit, the studio would approach Dustin Hoffmann to play Sonny. And every time, when Al heard Dustin might be replacing him, he'd come back to the film. Hilarious, huh? That's how it always worked. Al quits. Hey Dustin, you want to do it? Al comes back. How incredibly weird. Hollywood, I tell ya. I wonder what Dustin thought about that.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing Frank said tonight has to do with one of those tiny little changes he made that, when you see the film, doesn't seem like much, but which had a huge impact in real life. Toward the end of the film there's a scene where Sonny's out on the sidewalk talking to an FBI agent played by a young pre-sci-fi Lance Henrickson. He's Agent Murphy, based on a real Agent Murphy who helped bring an end to the standoff. When Murphy says they're getting a limo to take them to JFK, he's like, "You just let us worry about Sal." With that one statement, Murphy's trying to get Sonny to sell out Sal. At first Sonny's indignant as hell, but Murphy remains calm. "You just let us worry about Sal." Sonny doesn't say anything, he just goes back inside the bank to wait for the limo with everyone else. Sal wants to know what Sonny was saying to the agent. He's been suspicious as hell throughout the movie and demands to know why Sonny and Murphy were talking in hushed tones. Sonny plays it off and makes something up. And then soon after, when Sonny's looking out the glass door, he makes eye contact with Murphy. They nod at each other. It's just one little gesture with which Sonny effectively sells out Sal.

In reality, John Wojtowicz did not sell out Sal. It was dramatic license on Frank's part. I can understand perfectly why he did it. It's one of those rules of thumb in storytelling that you have to have betrayal. You don't have to, but you do. There are no rules in writing, but there are. Betrayal is one of them. Now mind you, it doesn't have to be Caesar and Brutus. Most of the time it isn't. But it should at least alter the course of the story.

At the time the movie came out, John Wojtowicz was already locked up in Fort Leavenworth. He and the other inmates saw the movie. While he knew a lot of it was made up, his fellow inmates took it as 100% fact. So when they saw Sonny betray Sal in the movie, they assumed John betrayed the real Sal. The inmates were furious. Death threats were made. For John's safety, the warden had him locked up in solitary for no less than eighteen months. A year and a half of his life in solitary simply because of one nod by Al Pacino to Lance Henrickson. Amazing, huh? Frank, not surprisingly, still feels terrible about that. To his credit, though, when he was still working on the script, he tried several times to visit John in prison but to no avail. John apparently felt he wasn't being paid enough.

The studio paid John $7,500 for his story, which would be about $30,000 today. They also gave him 1% of the net profits, but that isn't much. Now if they said 1% of the gross, that would be different. One of my professors in film school couldn't have stressed that enough. She was an independent producer from Washington, D.C. She was like, net is basically nothing. It's gross or bust. At any rate, John gave $2,500 to his boyfriend Ernie so he could finally, at long last, become a woman. Once the surgery was done, he changed his name to Elizabeth Eden. The sad coda there is that she didn't last long after that. Elizabeth died of AIDS in Rochester in 1987.

One thing I didn't know until tonight was that John Wojtowicz's holdup of Chase Manhattan was the first time ever where you had live television coverage of a crime. We see this in movies all the time now. And in real life. But according to Frank, it had never happened before that fateful day in August of '72. Now that I think about it, it kind of makes sense. I remember watching a documentary about Telly Savalas many years ago on A&E or one of those c

hannels. They mentioned that the reason Kojak was such a groundbreaking TV show was because of all the on-location shooting they did on the streets of New York. Most pre-Kojak shows were studio bound. And if they did venture out, they usually wouldn't stray too far. The big reason for this was technology. Or lack thereof. In the late sixties you saw the advent of cameras that, while huge and bulky by today's nano standards, could at least be transported and lugged around with relative ease compared to the beforetimes. The producers of Kojak took great advantage of this. Kojak debuted in the fall of 1971. The events depicted in Dog Day Afternoon took place in August 1972. By this point, if studios had the more modern equipment, so would news outlets. When word got out that someone was holding up a bank in Gravesend, Brooklyn, the reporters and their cameramen could just grab the gear and go. And it's because of how new it all was, to cover a crime while it was taking place, that the cops didn't always keep it together. Several times we see the Charles Durning character, Moretti (based on the real lead detective from the scene, James McGowan), not always kept in the loop when small teams of cops are getting ready to shoot down Sonny or storm the back door. His control of the situation is compromised by these communication lapses. Plus you've got all those onlookers standing around, which the cops couldn't deal with. That one guy breaks through and tackles Sonny at one point. It was all such a mess. The cops had no idea how to handle it because there was no precedent.

hannels. They mentioned that the reason Kojak was such a groundbreaking TV show was because of all the on-location shooting they did on the streets of New York. Most pre-Kojak shows were studio bound. And if they did venture out, they usually wouldn't stray too far. The big reason for this was technology. Or lack thereof. In the late sixties you saw the advent of cameras that, while huge and bulky by today's nano standards, could at least be transported and lugged around with relative ease compared to the beforetimes. The producers of Kojak took great advantage of this. Kojak debuted in the fall of 1971. The events depicted in Dog Day Afternoon took place in August 1972. By this point, if studios had the more modern equipment, so would news outlets. When word got out that someone was holding up a bank in Gravesend, Brooklyn, the reporters and their cameramen could just grab the gear and go. And it's because of how new it all was, to cover a crime while it was taking place, that the cops didn't always keep it together. Several times we see the Charles Durning character, Moretti (based on the real lead detective from the scene, James McGowan), not always kept in the loop when small teams of cops are getting ready to shoot down Sonny or storm the back door. His control of the situation is compromised by these communication lapses. Plus you've got all those onlookers standing around, which the cops couldn't deal with. That one guy breaks through and tackles Sonny at one point. It was all such a mess. The cops had no idea how to handle it because there was no precedent.The moderator did try to squeeze in some Citizen Cohn questions at the end, but they were pretty much out of time. Frank said it was tough trying to tell a story about a guy who was such an unrelenting asshole. He did say that David Franzoni's script wasn't the final draft. A woman whose name I've forgotten took a pass at it before shooting began, but unfortunately her changes weren't enough to warrant screen credit. One awesome line she put in, Frank said, was at the end when Roy Cohn finally kicks the bucket. The doctor says to Cohn's boyfriend Peter: "Well at last he did something human."

Anyway, awesome event. Frank Pierson's one of the best speakers I've seen. Just to show you how weird life is, remember above when I mentioned Tony Kushner writing that one-act play G. David Schine in Hell? Well get this. When his play Angels in America was made into an HBO miniseries, guess who played Roy Cohn?

Al Pacino.